Understanding human behaviour is vital for good product design. But you can’t just ask people what they need, you have to observe them first-hand. iPods, eBay and TiVo exist because designers watched people, noticed a problem with current products, and designed a solution for a problem people didn’t even know they had.

At OXO Foods in the UK, researchers studied how people measure liquids while cooking, and noticed that most people need to bend down repeatedly to read the markings on the side of the container. None of them reported this as a problem when interviewed. So OXO designed a measuring jug(cup) which could be viewed from above (shown right). This is an example of the growing science of design ethnography – product design based on direct human observation.

How to measure human behaviour “in the wild”?

Observational studies are expensive to conduct, and sometimes distorted because you can’t always observe someone in their natural environment. Fortunately, computers now make it much easier to collect data from “real world” activities. Such data is invaluable – for product designers to better understand their users, and also for us to help us cultivate a deeper understanding of ourselves.

Consider a game designer who wants to improve the interface for her game. At HCI2010, I saw Dr Richard Lilley demonstrate the new i-View X technology from SensoMotoric Instruments, shown in the video below. This tracks the player’s gaze and records what part of the screen they are looking at.

As well as recording the game experience and user inputs, a webcam captures facial expressions. With this system, our designer can examine both qualitative and quantitive data to measure the impact of interface changes – such as repositioning an on-screen HUD – based on how much attention the user gives it and how it influences their play. The designer can develop the game systematically and improve it faster. By watching his own recordings, a player can learn and improve his skills quickly too – and this approach is already being applied in a variety of different sports. For both player and designer, the feedback cycle is shortened considerably.

Visualizing Gameplay Data for Deeper Understanding

At the same conference I met Alicia Dudek, an MSc Design Ethnographer from the University of Dundee, whose research explores ways to gain deeper understanding of how people play games. Your choices when playing a game are a combination of your personal circumstances and the way the game is designed, so both must be explored – but the first step is to identify behaviour patterns.

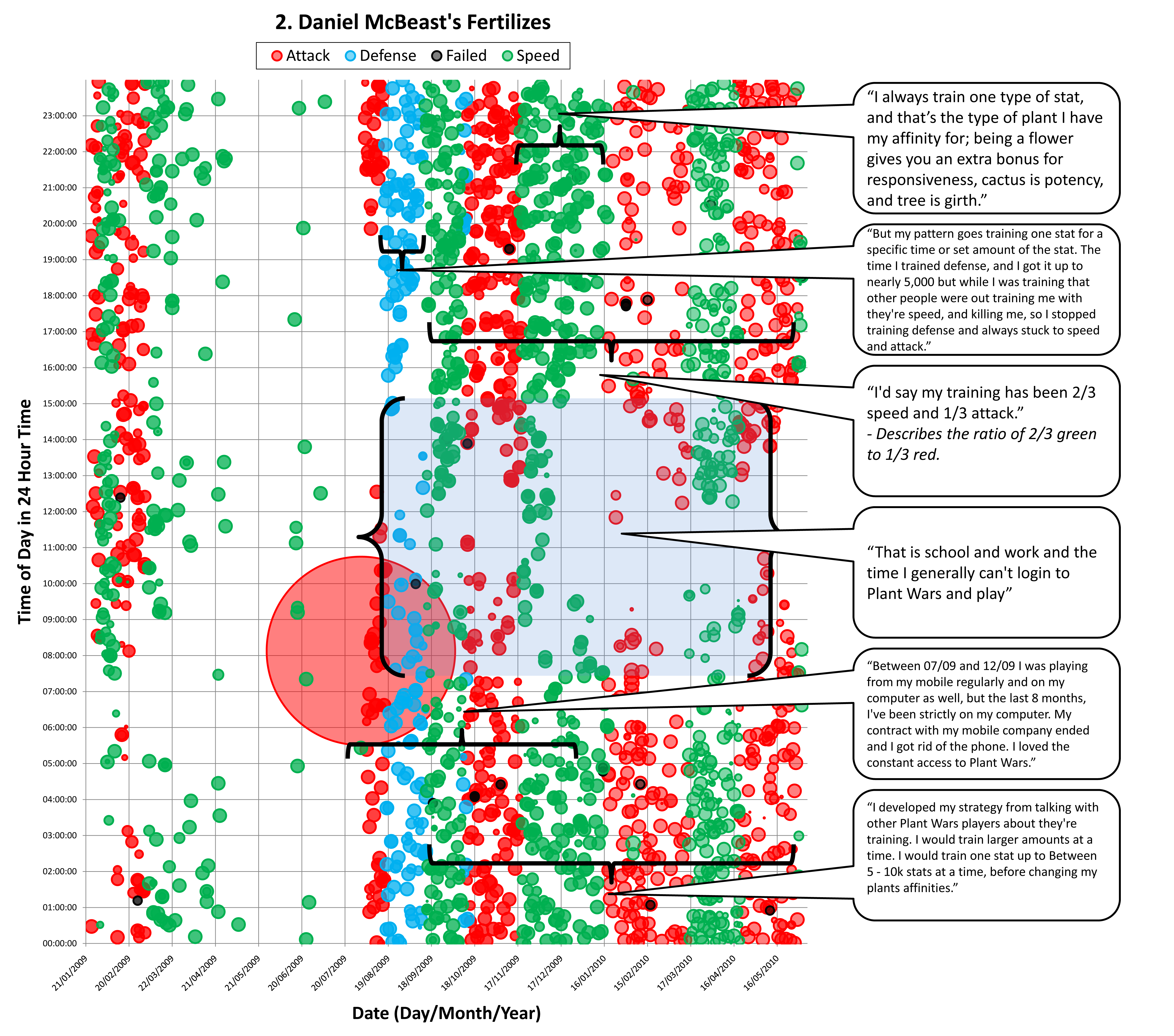

To do this, Alicia and her colleague Rachel Shadoan analysed 18 months of player histories from the web game Plant Wars. They plotted this data on a graph, with the vertical axis representing time of day, and the x axis representing the passage of time in weeks and months. Different activities in game are marked using dots of different colours and sizes at the appropriate time. Here is the visualization for one player: (Click the chart for a larger version.)

These graphs were used as the basis for player interviews, where key events were annotated with feedback from the player. Having these visual stimuli yielded more detail than relying on memory. Here we can see how the game rules, the player’s daily routine and even the device he used had measurable affects on his patterns of play. The study is detailed in full in this PDF.

From Gameplay to Real Life

Visualizing and explaining behaviour patterns will help designers create better games, but can they help players too? I asked Alicia where this research might lead in future:

“We create vast amounts of data about our behavior patterns, which over time form habits, altering us as people. We need to elevate our awareness of our intangible interactions. We cannot touch emails or feel battles in games. Our minds and ways of thinking are being restructured. Research like ours aims to make it easy to understand your behaviour without specialist training. One day you may be able to know not only what you’re getting good at in a games but also how it affects you.”

As we enter the age of metrics, games and sports are just the tip of the iceberg. Already you can track your computer usage, the language you use, or even your sex life! And the behavioural data we all generate daily is very valuable. Twitter and Google both collect and analyze your web surfing habits. And fraudsters want your behaviour data too. But a new generation of tools are emerging, with which we will explore and learn from our own behaviour data. In the future, our choices will be much better informed.

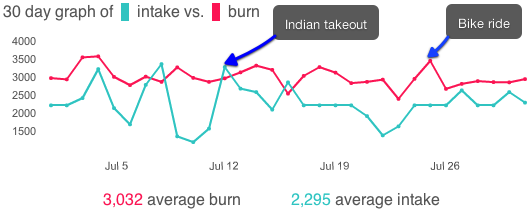

For example, with my Fitbit I can measure my calories burned and consumed and see it on a graph:

Right now, you need to add your own annotations. But it’s easy to imagine a tool that would let you annotate and interpret patterns like these. Your phone could even alert you when you’ve over-eaten and discourage you from making that restaurant booking.

As more data about our lives become available, we’ll gain new insights into our unconscious habits; computers will increase our awareness of ourselves. They’ll help us understand how music affects our mood, how our diet affects our work productivity, or how our sleeping habits affect our relationships. Life visualizations will empower us to make better decisions. The only caveat: As we use this new power to reduce many decisions to equations, we’ll need to be careful not to sideline those intangible, unmeasurable qualities like love, happiness and instinct.

Video by SensoMotoric Instruments. Graph by Alicia Dudek and Rachel Shadoan.

Thanks to Alicia Dudek and Richard Lilley for their input and ideas which contributed to this post.

@

@

Tags:

Tags:

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to