Part three: the problem with teachers’ unions

In this four-part series, we look at the impact of tablet computing on education: how tablets can save North American students, but how their ability to collect and analyze how students learn will make teaching more accountable — something that unions will oppose aggressively as they try to protect their members’ jobs.

This is a detailed write-up of the Short Bit I first presented at Bitnorth 2010, with lots of background and links to references I found while putting together that presentation. We decided to break it into several parts to make it easier to digest.

At this point in my research, as I explained in yesterday’s post, I’d concluded that learning isn’t a priority in North America — politically, culturally, or economically. It seems to me that tablets — with their access to affordable, tailored education — offer a tantalizing cure to the ills of North American’s classrooms, and a path to the digital classroom that can help us catch up with the rest of the world.

When I started looking into the issue of education in North America, I assumed that military spending outstripped healthcare and education dramatically. That’s how it is in many regions. In San Francisco, for example, 21% of a family’s taxes in 2007 paid for war, while just 5% went to education. Globalissues.org puts military spending — and the financing of past wars — at 44.4% of the US tax haul, with education just under 7%.

In absolute terms, the US pays a tremendous amount for its education (putting aside “special budgets” for specific wars). Universities in the US are the most expensive in the world, and despite spending all that money, the K-12 educational system is dysfunctional.

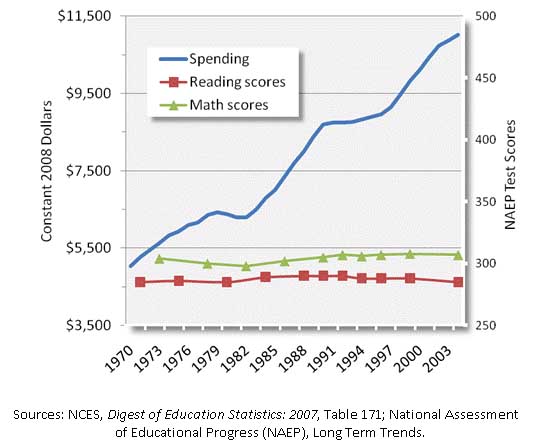

Comparing standardized test scores, spending on teachers in North America climbed dramatically while performance remained flat.

In other words, despite spending a lot on education, we aren’t seeing good results.

It’s not just lack of money, or inefficiency, which undermines US education. Some regions of the country, like Detroit and New Orleans, are still dealing with economic and environmental collapse. To make matters worse, the country is still trying to decide whether it should teach science or faith, redacting history, evolution, and climate change while adding God to the curriculum. The strangely gerrymandered economics of textbook manufacture means that Texas gets to decide what goes into the books the whole country reads. And Texas has decided to rewrite history.

But amazingly, hippy lefty liberal that I am, I don’t want to complain about any of these problems. And I don’t want to just pick on the US here: similar inefficiencies are creeping into the education system of other Western nations, including Canada and the UK.

Instead, I want to talk about the biggest threat to education: Teachers’ unions. Here’s the argument in a nutshell: When you learn from a tablet, it learns from you. What if it learns that your teacher can’t teach?

What makes great teachers?

The Gates Foundation set out to try and understand why US education was so broken (education is one of the foundation’s core areas of focus.) It turns out that the single most important factor in children’s performance is having great teachers. Simply put, if your teacher is in the top 25 percent of teachers, your test scores go up by 10 percent in a single year.

In other words, if the entire U.S. population had teachers ranked in the top 25 percent, the gap between US and Asian schools would vanish in a single year — and in four years, the U.S. would be far ahead of the rest of the planet.

Think about that for a minute: make more good teachers, fix the future of a nation.

Simple, right? You just need to find and encourage those top teachers: put them in charge, give them money, learn from them. Find out what makes them better, and reward that.

Unfortunately, that’s not how the system works. The foundation’s research showed that the only predictor of whether a teacher is in the top 25 percent — the percent that can save us — is that teacher’s past performance. Factors like whether a teacher has a master’s degree, or how long they’ve been teaching, have nothing to do with their students’ performance. And yet those are two things that have a big impact on teacher salary.

Guess what doesn’t get a teacher a raise? That’s right: being a good teacher. Worse, Gates’ team found that on average, the slightly better teachers leave the system early in their careers, meaning that the longer a teacher has been teaching (and the harder they are to fire), the less likely they are to be good.

Teachers’ unions have numbers and money

Terry Moe, a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution and the William Bennett Munro Professor of political science at Stanford University, says that “unions are and have long been major obstacles to real reform in the [educational] system.” Rod Paige, the U.S. Secretary of Education under the Bush administration, goes one further, calling them terrorist groups.

Unions have strength in numbers. 12 percent of the US workforce is unionized; but with teachers, it’s 38 percent. In New York City, 96 percent of people who teach are in the union. The two largest unions, the NEA and the AFT, have 4.6 million members between them.

They have money, too. The NEA alone had $400M in dues in 2007. As a teacher, you can’t just decide not to be a union member: in California, if you opt out, you get back $300 of your $1,000 annual fee, the union still gets $700, and you still have to play by their rules. They put the money they raise to good use, too: teachers’ unions are the top political spender in the US — contributing more than double what the runner-up did to elected leaders and lobbyists.

What about charter schools?

Some schools are trying to fix this, particularly those known as charter schools. By challenging traditional public school methods and focusing on student performance, charter schools have shown amazing results. These schools tend to embrace teacher data. They show colleagues what works and what doesn’t. They teach in teams. They focus on teaching well. The result? In one case of a charter school that Gates cites, 96 percent of high school graduates — from the poorest regions of America — went to college.

Since they’re a threat to unions, charter schools are under fire. There are 4,600 charter schools in the US and 90,000 public schools. Those charter schools have huge waiting lists — 11,000 students in Harlem applied for 2,000 open slots recently. So why not make more of them? Because the unions don’t like them.

In Detroit a few years ago, a donor offered to spend $200M to set up additional charter schools in what is one of the worst regions of the country. Unions shut down the schools, demonstrated in the state capitol, and convinced politicians to turn down the money.

Lobbying against accountability

It’s not just charter schools that are in the unions’ sights:

- In New York City, when schools suggested they were going to use student test scores as one factor in evaluating teachers for tenure, the unions convinced state legislators to pass a law making it illegal to use those scores in evaluating teachers for tenure anywhere in the state of New York.

- It happens at the national level, too: a recent US House stimulus bill included funding for data systems to track and improve teaching, but the Senate removed it under pressure.

- During layoffs, seniority rules mean that junior people get laid off before senior ones. This purges good teachers from the system, since effective teachers, statistically, are young teachers.

- Unions have even successfully limited the number of times a principal can come into the classroom, even requiring advance notice of visits.

- Jaime Escalante, (played by Edward James Olmos in the movie Stand and Deliver) taught college-level calculus to “unteachable” gang members in L.A. He allowed more students in his class than the union contract allowed, so he was run out of town by the union.

- Bill Evers, a reformer in California, wanted to try a new way of teaching math into his schools. The unions killed it because learning the new teaching method was too hard.

The list goes on. Frustrated parents and administrators have hundreds of stories of the union protecting its members at the expense of students’ education, even when those members’ behavior is indefensible.

When administrators do find a bad egg, unions make it impossible to remove the rot. Unions fight for all kinds of protections that make it incredibly difficult to fire a teacher. On average, it takes 2 years and $200,000, and 15 percent of a principal’s time to remove one bad teacher.

Unions go to great lengths to protect tenured members — so school boards sometimes put alleged sex offenders into a district office rather than firing them. According to Sand, this is commonplace: one union rep admitted to him, “I’ve gone in and defended teachers who shouldn’t even be pumping gas.”

Administrators are terrified of the unions’ power, and capitulate. According to as explained in a recent Freakonomics podcast on charter schools, only 13 percent of teachers in New York can get 80 percent of their students to pass. Yet 99 percent of teachers get a satisfactory rating from administrators.

If only 10 percent of teachers are downright awful — as we’d expect from a normal distribution of teaching talent, were we allowed to analyze it — that’s still 5 million children stuck in classrooms with awful teachers who can’t be replaced.

In the end, unions hate accountability, calling it “scapegoating” of teachers. Yet a 2004 study by the Thomas B. Fordham institute concluded that 21.5% of urban public school teachers sent their own kids to private school, compared with 17.5% of all urban families and only 12.2% of all families in the U.S. A 1983 study of Chicago public schools showed teachers were twice as likely to send their kids to a private school. And it’s not because teachers earn more — indeed, the Fordham study found that “as income decreases, a greater percentage of urban public school teachers choose private schools.”

How can this be good for kids?

Clearly, this is protecting bad teachers at the expense of a nation’s education. But the union’s massive membership numbers give teachers’ unions tremendous power to change how education happens, despite having no accountability for the results. Speak out against them, and you’re a pariah, on the receiving end of hate mail and accusations of class warfare (which this series of posts will undoubtedly earn.)

Both Gates and Moe ask an awkward question: would anyone organize education this way if their top priority was the improvement of young minds? Probably not. Imagine running a company, asks Gates, where you couldn’t use someone’s performance to decide whether they got promoted, and weren’t allowed to supervise your employees or learn and teach what worked best. Sadly, that’s the state of much of North American education.

Teachers know what schools are like, though.

Simply put, unions resist anything that might weaken the stranglehold they have on the future of a nation’s children, and with it, the future of a nation. So guess how they’re going to feel about the accountable, free, extensible classroom-of-one that tablets promise — a promise that could reverse the decline of the North American empire. That’s what we’ll look at next.

@

@

Tags:

Tags:

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to

[…] An analyzed, accountable education sounds great, unless you’re the largest political force in the US: Teacher’s unions. We’ll look at that in detail in the next post. […]

[…] In other words, tablets make teaching accountable, bringing to it the kind of clarity and can’t-argue-with-that science that has transformed online marketing. But as we saw yesterday, there are powerful forces terrified of what the harsh light of accountability will reveal, as we saw yesterday. […]