Before email, blogging and e-books, words were confined to the printed page. You would read the physical book in order from start to finish. But now we can now pull apart bodies of text, cross-reference them, share extracts, edit them and even plagiarize them, with unprecedented ease. With the advent of digital publishing we can analyze a body of text to see what words are used and how, using freely available online tools.

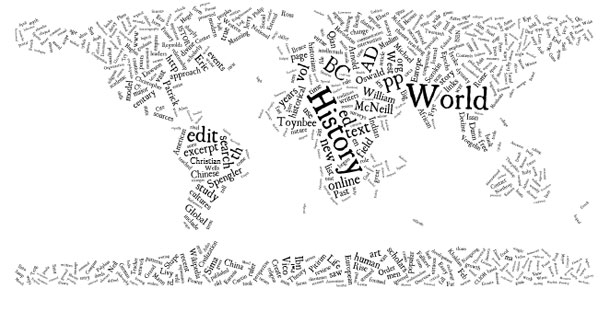

They say a picture’s worth a thousand words. But what’s a picture of a thousand words worth? Tag clouds – visual clusters of words where size denotes importance – have been used for everything from navigating blogs to finding popular photographs. They’re a must-have in Web 2.0. But when Jonathan Feinberg of IBM Research created Wordle in 2008, researchers and curious readers gained a new tool. You can generate a tag cloud of any body of text – from news articles or PhD theses to blog posts or whole books; here is a tag cloud of the Bible. The two most popular generators are Wordle and Tagxedo, but there are many alternatives.

Tag clouds can be used to quickly summarize the language used. For example, I generated this tag cloud of the coalition agreement between the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties in the UK using Wordle:

You can digest some things right away – clearly this is a document about topics the two parties agree on. Also, the Liberal Democrats and their preferred topics (Europe, referendum, welfare) seem prominent – could this indicate they dominated the negotiations?

We must be careful. Tag clouds don’t take into account the context – positive or negative – in which a word was used. The prominence of words like work, tax, or referendum does not tell us anything at-a-glance about the authors’ attitude toward those topics.

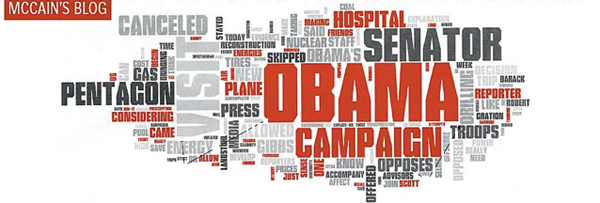

However, during the lead up to the US Presidential election, the Boston Globe used Wordle to analyze the blogs of the two main candidates, and were able to draw some interesting conclusions:

Here is their tag cloud of Obama’s blog:

Here is the tag cloud of McCain’s blog:

Here is the tag cloud of McCain’s blog:

We immediately see that McCain spent more words talking about Obama than any other topic – and that there are many more negative words in McCain’s cloud.

Tag clouds reveal a great deal about two sources when viewed side by side. A detailed analysis was published by the Globe, and a similar approach has been used to compare historical US presidential speeches.

Today, even people who don’t have a blog produce thousands of words digitally – in emails, on social networks and in text documents. Researchers can now make all sorts of interesting insights by analyzing people’s words in digital form. For example, Agatha Christie may have had Alzheimer’s. These tools are now available to everyone.

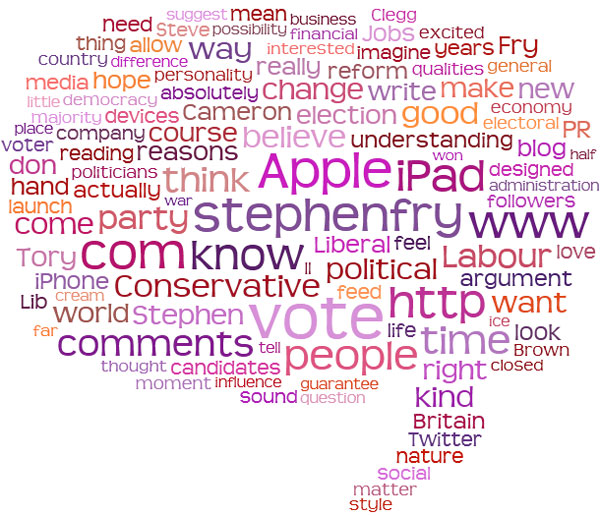

Here is a Tagxedo tag cloud generated from Stephen Fry’s blog:

Stephen writes a lot about the current events, such as the new UK government and the launch of the Apple iPad. Without ever meeting him or hearing him speak, you know that politics, technology and people are important to him. This is something employers in particular will find useful. With Wordle, you can even judge someone by the bookmarks they share on delicious – as my colleagues Roo Reynolds and Andy Piper have demonstrated.

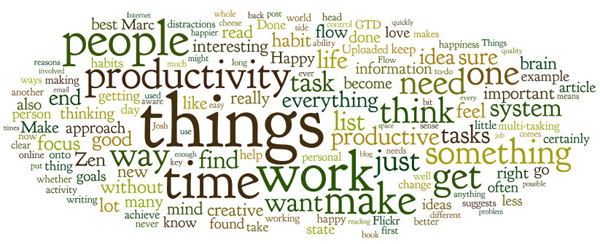

Here’s a useful exercise: Find the longest document you’ve ever written, and paste it into Wordle. The results can be enlightening. I generated this tag cloud based on my “Zen of Productivity” post from 2008:

I can tell straight away that I over-use the word “things” and “something” and that I use simple words like “get”, “find”, “work” “want” and “make” heavily (which may or may not be a good thing). I can also tell that I favour analytical words like “think” and “system” over emotive words like “feel”, “love” and “creative”. As a writer, such information can be invaluable – it can help you tailor your language to your audience.

Some words appear more than once – “Happy” and “happy”, “get” and “getting”, etc. Plurals and capitalizations are thought to be different words. For a more accurate tag cloud, you often need to weed your text first by finding and replacing occurrences of similar words with a single form – for example finding all occurrences of “needs” and replace them with “need”.

These simple analyses are just the tip of the iceberg. Already, researchers are harnessing the outputs from this explosion of digital literacy to solve all manner of problems from automatically detecting plagiarism to understanding how children develop syntax. Entire fields of linguistic study are now automated. As computers understand more of our words and the semantic web grows, it’s only a matter of time until tools empower every one of us as linguistic forensic scientists.

@

@

Tags:

Tags:

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to

Like all images on the site, the topic icons are based on images used under Creative Commons or in the public domain. Originals can be found from the following links. Thanks to

There's a connection here with a previous post (http://www.human20.com/i-know-what-you-liked-la…), using your tag cloud to fingerprint you in spite of your attempts to stay private. The more participatory we get, the easier it'll get to identify us by our writing. I'm going to start using “things” more often.

[…] games and sports are just the tip of the iceberg. Already you can track your computer usage, the language you use, or even your sex life! And the behavioural data we all generate daily is very valuable. Twitter […]

I’d like to see how these tag clouds look after defining a word and then defining another word within the given definition repeated 3 or 4 times. Dig deep! “Things” become “stuff” which morphs to “tangible”…? Who knows the outcome!

[…] What do your words say about you examined how each of us is now empowered to do our own analysis of authors and public speakers using tag clouds: We all produce more words digitally than ever before. With free tag cloud generators, anyone can analyze your language and learn a great deal about you in just a few seconds. The age of digital linguistics has begun. […]